Burma's Most Wanted

By LESLIE HOOK

February 2, 2008; Page A11

Mae Sot, Thailand

'We did not reach final victory. We were defeated in the middle of our struggle," says the young Burmese monk sitting in front of me. "It will be very hard to have another demonstration."

He should know. Ashin Kovida chaired the impromptu committee that organized last year's democracy protests in Rangoon, Burma. The marches, sparked by an economic crisis, brought more than 100,000 people to the streets to demand democracy and the release of political prisoners, including opposition leader and Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. The ensuing crackdown left at least 31 civilians dead, and thousands more beaten or jailed.

The protest leaders -- Mr. Ashin included -- fled for their lives. Exchanging his monks' robes for civilian clothes and a crucifix necklace, Mr. Ashin hid in a shack outside Rangoon for several weeks. After he made it over the border into Mae Sot, Mr. Ashin holed up in a safe house, leaving only to be shuttled to occasional meetings or interviews. Finding a safe venue for our meeting proved a challenge. We agreed I'd wait in my hotel for a phone call from a "friend," who would tell me how to proceed. "There are many different kinds of people at your hotel," Mr. Ashin said. "Maybe not safe."

When our agreed interview time passed, I worried if he'd been snagged by the Burmese spies trawling this town. An hour later, there was a soft knock on my door. When I opened it two men scuttled inside: Mr. Ashin, a skinny 24-year-old in flame-colored robes, and Kyaw Lin, a friend and interpreter. The monk looked horrified when I shook his hand, averting his gaze. It's only afterward that I realized this violated his vows to touch a woman.

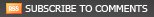

Mr. Ashin had no special preparation to become a freedom fighter; if anything, he had a typical, impoverished Burmese childhood. Born in 1983 in a village near Ann, a town in the eastern state of Arakan, he joined a monastery at age 12. His parents were farmers, and they sent him, their second son, to become a monk at the nearest monastery so that he could get an education. He lived there until 2003, then moved to Nan Oo monastery in Rangoon to pursue further monastic studies.

Meanwhile, his country was falling into grave disrepair. Since the junta took power in 1962, the generals have stripped the country for their own personal gain through a combination of brutal oppression, continuing ethnic wars, and a massive standing army of more than 400,000 soldiers. Today it is difficult for most citizens to obtain basic food and clothing. Per capita GDP is around $300, in league with the world's poorest countries.

Political activism in this environment is difficult, at best. But monks in Burma have a tradition of being involved. Their daily alms rounds keep them in touch with citizens' lives, and their vows require them to act for the well-being of their community. In 1988, when students and citizens took to the streets to protest for democracy, the monks marched alongside them. Those demonstrations ended with the massacre of several thousand demonstrators.

But the way he tells it, Mr. Ashin's activism wasn't originally part of a national movement; rather, it evolved from a grass-roots level, organically. After several monks were beaten during a Sept. 5 protest in Pakokku, a city in central Burma, Mr. Ashin and his fellow monks were so outraged that they printed and distributed pamphlets demanding an apology from the government. Mr. Ashin says he spent Sept. 10-13 wandering the streets of Rangoon with a bag full of pamphlets, distributing them to major monasteries.

"We demanded that the government apologize [for what happened in Pakokku]," Mr. Ashin explains. "If there was no apology by Sept. 18, then the monks would take to the streets. On Sept. 18 there was no response. On Sept. 19, my colleagues and I thought we needed an organization to organize the protests and keep them on the right track."

Thus the Sangha (Monks) Representative Committee -- an organization that would soon become the nexus of the demonstrations in Rangoon -- was born. The committee was composed of 15 volunteer monks, aged 24-28, who had met each other during earlier protests in August and September. "Everyone was invited," Mr. Ashin says. "I did not even know the names of the others -- most of them used nicknames for their security."

Mr. Ashin was elected chairman, and the committee agreed to meet every morning at 9 a.m. at the East gate of the Shwedagon Pagoda -- Burma's holiest shrine and the temple from which Aung San Suu Kyi addressed her followers during the protests of 1988. Its purpose?

"The committee was there to control the demonstrations and make sure they were peaceful," he tells me. They wanted "just to help the people, and to show how much people are suffering. The monks did not have any political objectives. We want for people to have a right to fight for power . . . the monks just paved the way for them."

Unlike 1988, the monks had new tools available to help their cause. Cell phones and the Internet played a crucial role in enabling the protests, and in alerting the outside world. All of the recent arrivals I met in Mae Sot, including Mr. Ashin, said they used Gmail chat ("gtalk," they call it) to keep in touch with their friends and family inside Burma. Yahoo! is blocked inside Burma.

To avoid confrontation with the government, the organizing committee asked people not to display any signs or flags other than the "sasana," a Buddhist flag used in religious ceremonies. The committee also had a practical function: to ensure that monks, who gather alms in the morning for food, could forego that duty to walk into the city center and join the marches (some walked for hours to get there). "All classes of people joined together to prepare food," he says, adding that famous Burmese actors and models pitched in, too.

It was a grass-roots political movement from the start. Mr. Ashin says none of his colleagues were members of any political groups. No one on the committee had contact with Ms. Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy until the party asked the committee for permission to display its flag, he says.

A few days after the committee formed, representatives from the NLD and some student political groups did ask. And so the yellow phoenix -- a sign of NLD unity during 1988 -- was displayed on the streets of Rangoon once again. The committee also allowed public speeches on Sept. 25.

For the military junta, that was a step too far. That night, the first of a series of brutal midnight raids on monasteries began.

The next morning, only seven of the 15 committee members showed up at their meeting place, Mr. Ashin says. As people came out to march, they found that the military had cordoned off the areas around Shwedagon Pagoda where they usually met. Disjointed groups began to coalesce, and Mr. Ashin said he found himself in the midst of about 300 people surrounded by walls and riot police. The police tried at first to persuade the protesters to let them "take them home" -- which the protesters understood to mean arrest -- and then began forcibly arresting protesters.

Mr. Ashin remembers that as a dark afternoon. He himself received several blows to the stomach before he scaled a wall to safety. "The monks and students started throwing stones at the security forces. There was a violent mood. [People from the committee] tried to convince people to stop and not be violent."

Across the rest of Rangoon similar scenes played out. In some places soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators, and day's end saw dozens dead or wounded.

On Sept. 27, the committee couldn't meet at all. Some people tried to continue the protests, but a massive security presence resulted in further violent clashes. That night, Mr. Ashin took off his robes and went into hiding.

The government didn't forget about him, though. State-run newspapers carried his photograph and labeled him a "fake monk." The junta's English mouthpiece, the New Light of Myanmar, accused him of being responsible for 48 cartridges of TNT found buried near a residence in Rangoon. While he was in hiding in a suburb, police canvassed nearby streets, searching for him.

Contrary to the propaganda the regime conjures up, Mr. Ashin says he was completely unconnected to the Burmese governments-in-exile that has sprung up in Thailand. He left Rangoon without a backup plan, and arrived in Mae Sot with a single phone number of a man he had never met.

Mr. Ashin is clearly devastated by what he perceives as the "failure" and the "defeat" of the protests. But most of his disappointment is directed not at the lackluster efforts of the United Nations -- "people outside seem to forget about Burma," he says -- but at his fellow Burmese.

"If the MPs had been actively involved, then our demonstrations could have changed something," he says. "It is a great loss for our struggle. But they were just watching and waiting." It's also evidence of how well the junta has done its cruel job that the massive street protests did not result in mass defections from the civil service or army, and saw almost no support from politicians in power.

Four months after the demonstrations Burma has largely fallen off of the world's radar screen. The U.S. and the EU were quick to implement tighter economic sanctions on the regime after the protests, but for Burma's major trading partners, it's been business as usual. Neighboring China, Thailand and India were all reluctant to comment on the events inside Burma, and have avoided putting pressure on the regime. The U.N. Security Council issued a statement "strongly deploring" the use of violence.

The situation on the ground in Burma is every bit as dire now as it was in September, and many say it is getting even worse, as fuel and food shortages continue.

Mr. Ashin's group, the Monks' Representative Committee, reorganized in several cities inside Burma earlier this year with 50 new members. They've issued a statement pledging to protest again this month if the government doesn't take action for political reconciliation. But with leaders like Mr. Ashin out of the picture and the junta on the lookout, it's difficult for them even to meet.

Mr. Ashin says he will be relocated to the U.S. soon, where he has been granted political asylum. He wants to continue working to bring change to Burma, but isn't sure how he will do so from a distant shore. Step one will be improving his English, so that he can tell the world what is going on.

Ms. Hook is an editorial page writer for The Wall Street Journal Asia.

ast-forward to 2011, when following his bliss leads Durkin, now a San Diego-based filmmaker, to the Burmese border to finish shooting a documentary on how art can change the world. At least that’s the ending he has in mind.

ast-forward to 2011, when following his bliss leads Durkin, now a San Diego-based filmmaker, to the Burmese border to finish shooting a documentary on how art can change the world. At least that’s the ending he has in mind.